Wayland from the Wire

2023-12-18To write a graphical application for Wayland, you need to connect to a Wayland server, make a window, and render something to it. This protocol is – for the most part – well specified, and by using nothing but linux syscalls you can gain a deeper understanding of how it all works.

This is an article I began writing while I was developing Shimizu. If you want a pure Zig library for making Wayland applications, check it out! This article will not teach you how to use Shimizu. Instead this article focuses on understanding Wayland at the level of bytes sent over the wire.

You can find the complete code for this post in the same repository, under examples/00_client_connect.zig. It was written using zig 0.11.0.

This article will focus on software rendering. Creating an OpenGL or Vulkan context is left as an exercise for the reader and other articles.

If you enjoy this post you may want to check out this talk by Johnathan Marler where he does a similar thing for X11.

By the end of this series, you should have a window that looks like this:

Connecting to the Display Server

The first thing we need to do is establish a connection to the display server. Wayland Display servers are accessible via Unix Domain sockets, at a path specified via an environment variable or a predefined location. Let’s start with a function to get the display socket path inside main.zig:

pub fn getDisplayPath(gpa: std.mem.Allocator) ![]u8 {

const xdg_runtime_dir_path = try std.process.getEnvVarOwned(gpa, "XDG_RUNTIME_DIR");

defer gpa.free(xdg_runtime_dir_path);

const display_name = try std.process.getEnvVarOwned(gpa, "WAYLAND_DISPLAY");

defer gpa.free(display_name);

return try std.fs.path.join(gpa, &.{ xdg_runtime_dir_path, display_name });

}

Now we can use the path to open a connection to the server.

const std = @import("std");

pub fn main() !void {

var general_allocator = std.heap.GeneralPurposeAllocator(.{}){};

defer _ = general_allocator.deinit();

const gpa = general_allocator.allocator();

const display_path = try getDisplayPath(gpa);

defer gpa.free(display_path);

std.log.info("wayland display = {}", .{std.zig.fmtEscapes(display_path)});

const socket = try std.net.connectUnixSocket(display_path);

defer socket.close();

}

Running this program will find the display path, log it, open a socket and then exit.

Listening for Globals

Now that the socket is open, we are going to construct and send two packets over it. The first packet will get the wl_registry and bind it to an id. The second packet tells the server to send a reply to the client.

Wayland messages require knowing the schema before hand. You can see a description of the various protocols here.

The first message will be a Request on a wl_display object. Wayland specifies that every connection will automatically get a wl_display object assigned to the id 1.

// in `main`

const display_id = 1;

var next_id: u32 = 2;

// reserve an object id for the registry

const registry_id = next_id;

next_id += 1;

try socket.writeAll(std.mem.sliceAsBytes(&[_]u32{

// ID of the object; in this case the default wl_display object at 1

1,

// The size (in bytes) of the message and the opcode, which is object specific.

// In this case we are using opcode 1, which corresponds to `wl_display::get_registry`.

//

// The size includes the size of the header.

(0x000C << 16) | (0x0001),

// Finally, we pass in the only argument that this opcode takes: an id for the `wl_registry`

// we are creating.

registry_id,

}));

Now we create the second packet, a wl_display sync request. This will let us loop until the server has finished sending us global object events.

// create a sync callback so we know when we are caught up with the server

const registry_done_callback_id = next_id;

next_id += 1;

try socket.writeAll(std.mem.sliceAsBytes(&[_]u32{

display_id,

// The size (in bytes) of the message and the opcode.

// In this case we are using opcode 0, which corresponds to `wl_display::sync`.

//

// The size includes the size of the header.

(0x000C << 16) | (0x0000),

// Finally, we pass in the only argument that this opcode takes: an id for the `wl_registry`

// we are creating.

registry_done_callback_id,

}));

We have to allocate ids as we go, because the wayland protocol only allows ids to be one higher than the highest id previously used.

The next step is listening for messages from the server. We’ll start by reading the header, which is 2 32-bit words containing the object id, message size, and opcode (same as the Request header we sent to the server earlier). This time we’ll create an extern struct to read the bytes into.

/// A wayland packet header

const Header = extern struct {

object_id: u32 align(1),

opcode: u16 align(1),

size: u16 align(1),

pub fn read(socket: std.net.Stream) !Header {

var header: Header = undefined;

const header_bytes_read = try socket.readAll(std.mem.asBytes(&header));

if (header_bytes_read < @sizeOf(Header)) {

return error.UnexpectedEOF;

}

return header;

}

};

And while we’re at it, we might as well make some code to abstract reading Events, as we’ll need it later.

/// This is the general shape of a Wayland `Event` (a message from the compositor to the client).

const Event = struct {

header: Header,

body: []const u8,

pub fn read(socket: std.net.Stream, body_buffer: *std.ArrayList(u8)) !Event {

const header = try Header.read(socket);

// read bytes until we match the size in the header, not including the bytes in the header.

try body_buffer.resize(header.size - @sizeOf(Header));

const message_bytes_read = try socket.readAll(body_buffer.items);

if (message_bytes_read < body_buffer.items.len) {

return error.UnexpectedEOF;

}

return Event{

.header = header,

.body = body_buffer.items,

};

}

};

With functions we defined above, the general shape of our loop looks like this:

// create a ArrayList that we will read messages into for the rest of the program

var message_bytes = std.ArrayList(u8).init(gpa);

defer message_bytes.deinit();

while (true) {

const event = try Event.read(socket, &message_buffer);

// TODO: check what events we received

}

First, let’s check if we’ve received the sync callback. We’ll exit the loop as soon as we see it:

while (true) {

const event = try Event.read(socket, &message_buffer);

// Check if the object_id is the sync callback we made earlier

if (event.header.object_id == registry_done_callback_id) {

// No need to parse the message body, there is only one possible opcode

break;

}

}

Next, let’s abstract writing to the socket a bit, so we don’t have to manually construct the header each time:

/// Handles creating a header and writing the request to the socket.

pub fn writeRequest(socket: std.net.Stream, object_id: u32, opcode: u16, message: []const u32) !void {

const message_bytes = std.mem.sliceAsBytes(message);

const header = Header{

.object_id = object_id,

.opcode = opcode,

.size = @sizeOf(Header) + @as(u16, @intCast(message_bytes.len)),

};

try socket.writeAll(std.mem.asBytes(&header));

try socket.writeAll(message_bytes);

}

Now we check for the registry global event, and parse out the parameters:

// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_registry:event:global

const WL_REGISTRY_EVENT_GLOBAL = 0;

if (event.header.object_id == registry_id and event.header.opcode == WL_REGISTRY_EVENT_GLOBAL) {

// Parse out the fields of the global event

const name: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[0..4].*);

const interface_str_len: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[4..8].*);

// The interface_str is `interface_str_len - 1` because `interface_str_len` includes the null pointer

const interface_str: [:0]const u8 = event.body[8..][0 .. interface_str_len - 1 :0];

const interface_str_len_u32_align = std.mem.alignForward(u32, interface_str_len, @alignOf(u32));

const version: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[8 + interface_str_len_u32_align ..][0..4].*);

// TODO: match the interfaces

}

We are looking for three global objects: wl_shm, wl_compositor, and xdg_wm_base. This is the minimum set of protocols we need to create a window with a framebuffer. These global objects also have a version field, which allow us to check if the compositor supports the protocol versions we are targeting. Let’s define our targeted versions as constants:

/// The version of the wl_shm protocol we will be targeting.

const WL_SHM_VERSION = 1;

/// The version of the wl_compositor protocol we will be targeting.

const WL_COMPOSITOR_VERSION = 5;

/// The version of the xdg_wm_base protocol we will be targeting.

const XDG_WM_BASE_VERSION = 2;

In addition, let’s create some variables outside of the loop so we can check if the global objects were found afterwards.

var shm_id_opt: ?u32 = null;

var compositor_id_opt: ?u32 = null;

var xdg_wm_base_id_opt: ?u32 = null;

To bind the wl_shm global object to a client id, we need to do the following:

- Check that

interface_stris equal to"wl_shm" - Make sure that the

versionisWL_SHM_VERSIONor higher. - Send

wl_registry:bindrequest to the compositor

Now, the wl_registry:bind request is a bit tricky. Unlike other request’s with a new_id that we’ve seen, it does not specify a specific type in the protocol! This means we must tell the server which interface we are binding in the request. Instead of sending a simple u32 for the id, we send 3 parameters, (new_id: u32, interface: string, version: u32). This make 4 parameters when we include the “numeric name” parameter.

if (std.mem.eql(u8, interface_str, "wl_shm")) {

if (version < WL_SHM_VERSION) {

std.log.err("compositor supports only {s} version {}, client expected version >= {}", .{ interface_str, version, WL_SHM_VERSION });

return error.WaylandInterfaceOutOfDate;

}

shm_id_opt = next_id;

next_id += 1;

try writeRequest(socket, registry_id, WL_REGISTRY_REQUEST_BIND, &[_]u32{

// The numeric name of the global we want to bind.

name,

// `new_id` arguments have three parts when the sub-type is not specified by the protocol:

// 1. A string specifying the textual name of the interface

"wl_shm".len + 1, // length of "wl_shm" plus one for the required null byte

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "wl_s".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "hm\x00\x00".*)), // we have two 0x00 bytes to align the string with u32

// 2. The version you are using, affects which functions you can access

WL_SHM_VERSION,

// 3. And the `new_id` part, where we tell it which client id we are giving it

shm_id_opt.?,

});

}

Writing out the entire loop we get this:

while (true) {

const event = try Event.read(socket, &message_buffer);

// Parse event messages based on which object it is for

if (event.header.object_id == registry_done_callback_id) {

// No need to parse the message body, there is only one possible opcode

break;

}

if (event.header.object_id == registry_id and event.header.opcode == WL_REGISTRY_EVENT_GLOBAL) {

// Parse out the fields of the global event

const name: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[0..4].*);

const interface_str_len: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[4..8].*);

// The interface_str is `interface_str_len - 1` because `interface_str_len` includes the null pointer

const interface_str: [:0]const u8 = event.body[8..][0 .. interface_str_len - 1 :0];

const interface_str_len_u32_align = std.mem.alignForward(u32, interface_str_len, @alignOf(u32));

const version: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[8 + interface_str_len_u32_align ..][0..4].*);

// Check to see if the interface is one of the globals we are looking for

if (std.mem.eql(u8, interface_str, "wl_shm")) {

if (version < WL_SHM_VERSION) {

std.log.err("compositor supports only {s} version {}, client expected version >= {}", .{ interface_str, version, WL_SHM_VERSION });

return error.WaylandInterfaceOutOfDate;

}

shm_id_opt = next_id;

next_id += 1;

try writeRequest(socket, registry_id, WL_REGISTRY_REQUEST_BIND, &[_]u32{

// The numeric name of the global we want to bind.

name,

// `new_id` arguments have three parts when the sub-type is not specified by the protocol:

// 1. A string specifying the textual name of the interface

"wl_shm".len + 1, // length of "wl_shm" plus one for the required null byte

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "wl_s".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "hm\x00\x00".*)), // we have two 0x00 bytes to align the string with u32

// 2. The version you are using, affects which functions you can access

WL_SHM_VERSION,

// 3. And the `new_id` part, where we tell it which client id we are giving it

shm_id_opt.?,

});

} else if (std.mem.eql(u8, interface_str, "wl_compositor")) {

if (version < WL_COMPOSITOR_VERSION) {

std.log.err("compositor supports only {s} version {}, client expected version >= {}", .{ interface_str, version, WL_COMPOSITOR_VERSION });

return error.WaylandInterfaceOutOfDate;

}

compositor_id_opt = next_id;

next_id += 1;

try writeRequest(socket, registry_id, WL_REGISTRY_REQUEST_BIND, &[_]u32{

name,

"wl_compositor".len + 1, // add one for the required null byte

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "wl_c".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "ompo".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "sito".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "r\x00\x00\x00".*)),

WL_COMPOSITOR_VERSION,

compositor_id_opt.?,

});

} else if (std.mem.eql(u8, interface_str, "xdg_wm_base")) {

if (version < XDG_WM_BASE_VERSION) {

std.log.err("compositor supports only {s} version {}, client expected version >= {}", .{ interface_str, version, XDG_WM_BASE_VERSION });

return error.WaylandInterfaceOutOfDate;

}

xdg_wm_base_id_opt = next_id;

next_id += 1;

try writeRequest(socket, registry_id, WL_REGISTRY_REQUEST_BIND, &[_]u32{

name,

"xdg_wm_base".len + 1,

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "xdg_".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "wm_b".*)),

@bitCast(@as([4]u8, "ase\x00".*)),

XDG_WM_BASE_VERSION,

xdg_wm_base_id_opt.?,

});

}

continue;

}

}

Let’s ensure that we have all the necessary global objects.

const shm_id = shm_id_opt orelse return error.NeccessaryWaylandExtensionMissing;

const compositor_id = compositor_id_opt orelse return error.NeccessaryWaylandExtensionMissing;

const xdg_wm_base_id = xdg_wm_base_id_opt orelse return error.NeccessaryWaylandExtensionMissing;

std.log.debug("wl_shm client id = {}; wl_compositor client id = {}; xdg_wm_base client id = {}", .{ shm_id, compositor_id, xdg_wm_base_id });

Now, assuming you’ve followed along, running the program with zig run main.zig should give output similar to the following:

$ zig run main.zig

debug: wl_shm client id = 4; wl_compositor client id = 5; xdg_wm_base client id = 6

Creating a Toplevel Surface

Creating a window is not complicated, but it does take several steps:

- Create a

wl_surfaceusingwl_compositor:create_surface - Assign that

wl_surfaceto thexdg_surfacerole usingxdg_wm_base:get_xdg_surface - Assign that

xdg_surfaceto thexdg_toplevelrole usingxdg_surface:get_toplevel - Commit the changes to the

wl_surface - Wait for an

xdg_surface:configureevent to arrive before trying to attach a buffer to it

The protocol description of wl_compositor:create_surface is straightforward:

wl_compositor::create_surface(id: new_id<wl_surface>)

All we have to do is bind a wl_surface to a client-side id.

// Create a surface using wl_compositor::create_surface

const surface_id = next_id;

next_id += 1;

// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_compositor:request:create_surface

const WL_COMPOSITOR_REQUEST_CREATE_SURFACE = 0;

try writeRequest(socket, compositor_id, WL_COMPOSITOR_REQUEST_CREATE_SURFACE, &[_]u32{

// id: new_id<wl_surface>

surface_id,

});

Steps 2, 3, and 4 are similarly simple:

xdg_wm_base::get_xdg_surface(id: new_id<xdg_surface>, surface: object<wl_surface>)

xdg_wm_base::get_toplevel(id: new_id<xdg_toplevel>)

wl_surface::commit()

// Create an xdg_surface

const xdg_surface_id = next_id;

next_id += 1;

// https://wayland.app/protocols/xdg-shell#xdg_wm_base:request:get_xdg_surface

const XDG_WM_BASE_REQUEST_GET_XDG_SURFACE = 2;

try writeRequest(socket, xdg_wm_base_id, XDG_WM_BASE_REQUEST_GET_XDG_SURFACE, &[_]u32{

// id: new_id<xdg_surface>

xdg_surface_id,

// surface: object<wl_surface>

surface_id,

});

// Get the xdg_surface as an xdg_toplevel object

const xdg_toplevel_id = next_id;

next_id += 1;

// https://wayland.app/protocols/xdg-shell#xdg_surface:request:get_toplevel

const XDG_SURFACE_REQUEST_GET_TOPLEVEL = 1;

try writeRequest(socket, xdg_surface_id, XDG_SURFACE_REQUEST_GET_TOPLEVEL, &[_]u32{

// id: new_id<xdg_surface>

xdg_toplevel_id,

});

// Commit the surface. This tells the compositor that the current batch of

// changes is ready, and they can now be applied.

// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_surface:request:commit

const WL_SURFACE_REQUEST_COMMIT = 6;

try writeRequest(socket, surface_id, WL_SURFACE_REQUEST_COMMIT, &[_]u32{});

Step 5 takes a bit more code and a little more effort to understand. Let’s first go over why we needed to call wl_surface::commit.

The xdg_surface documentation says the following:

A role must be assigned before any other requests are made to the xdg_surface object.

The client must call wl_surface.commit on the corresponding wl_surface for the xdg_surface state to take effect.

What this means is we must first send a request that assigns a role (like xdg_surface::get_toplevel), and then put that role into effect by committing the surface (using wl_surface::commit).

Even then we aren’t allowed to attach a buffer until we respond to a configure event:

After creating a role-specific object and setting it up, the client must perform an initial commit without any buffer attached. The compositor will reply with initial wl_surface state such as wl_surface.preferred_buffer_scale followed by an xdg_surface.configure event. The client must acknowledge it and is then allowed to attach a buffer to map the surface.

To wait for the configure event we create another while loop:

// Wait for the surface to be configured before moving on

while (true) {

const event = try Event.read(socket, &message_buffer);

// TODO: match events by object_id and opcode

}

We can then check if the event is a configure event meant for our xdg_surface object:

if (event.header.object_id == xdg_surface_id) {

switch (event.header.opcode) {

// https://wayland.app/protocols/xdg-shell#xdg_surface:event:configure

0 => {

// TODO

},

}

}

An xdg_surface::configure event must be responded to with xdg_surface::ack_configure:

# We must respond to this event:

xdg_surface::configure(serial: uint)

# With this request:

xdg_surface::ack_configure(serial: uint)

# Followed by another commit:

wl_surface::commit()

// The configure event acts as a heartbeat. Every once in a while the compositor will send us

// a `configure` event, and if our application doesn't respond with an `ack_configure` response

// it will assume our program has died and destroy the window.

const serial: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[0..4].*);

try writeRequest(socket, xdg_surface_id, XDG_SURFACE_REQUEST_ACK_CONFIGURE, &[_]u32{

// We respond with the number it sent us, so it knows which configure we are responding to.

serial,

});

try writeRequest(socket, surface_id, WL_SURFACE_REQUEST_COMMIT, &[_]u32{});

// The surface has been configured! We can move on

break;

All together, it looks like this:

while (true) {

const event = try Event.read(socket, &message_buffer);

if (event.header.object_id == xdg_surface_id) {

switch (event.header.opcode) {

// https://wayland.app/protocols/xdg-shell#xdg_surface:event:configure

0 => {

// The configure event acts as a heartbeat. Every once in a while the compositor will send us

// a `configure` event, and if our application doesn't respond with an `ack_configure` response

// it will assume our program has died and destroy the window.

const serial: u32 = @bitCast(event.body[0..4].*);

try writeRequest(socket, xdg_surface_id, XDG_SURFACE_REQUEST_ACK_CONFIGURE, &[_]u32{

// We respond with the number it sent us, so it knows which configure we are responding to.

serial,

});

try writeRequest(socket, surface_id, WL_SURFACE_REQUEST_COMMIT, &[_]u32{});

// The surface has been configured! We can move on

break;

},

else => return error.InvalidOpcode,

}

}

}

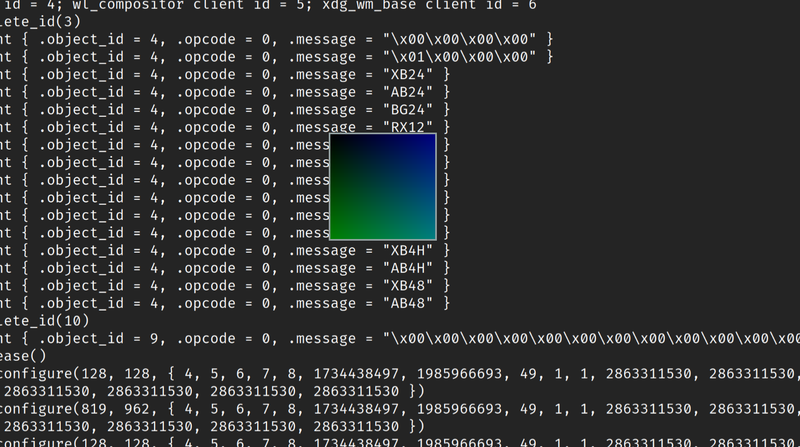

Now, one thing I like to do (but isn’t necessary) is add an else statement that prints out the events that we are not handling:

if (event.header.object_id == xdg_surface_id) {

// -- snip --

} else {

std.log.warn("unknown event {{ .object_id = {}, .opcode = {x}, .message = \"{}\" }}", .{ event.header.object_id, event.header.opcode, std.zig.fmtEscapes(std.mem.sliceAsBytes(event.body)) });

}

This makes it easier to debug if something goes wrong.

Creating a Framebuffer

Like creating a window, this section requires several steps. However, these steps are not as straight-forward as the steps for creating a window. We won’t need to create another loop (besides some kind of main loop), but we do need to understand some Linux syscalls.

The steps to create a framebuffer are as follows:

- Create a shared memory file using

memfd_create - Allocate space in the shared memory file using

ftruncate - Create a shared memory pool using

wl_shm::create_pool - Allocate a

wl_bufferfrom the shared memory pool usingwl_shm_pool::create_buffer

Steps 1 and 2: Allocating a memory backed file

Steps 1 and 2 require interfacing with the Linux kernel, and luckily for us the Zig standard library already implements these functions:

std.os.memfd_create(name: []const u8, flags: u32) !fd_tstd.os.ftruncate(fd: fd_t, length: u64) TruncateError!void

Before we make use of those functions let’s do some math to figure out how much memory we should allocate. For this article, we are only going to support a 128x128 argb888 framebuffer.

const Pixel = [4]u8;

const framebuffer_size = [2]usize{ 128, 128 };

const shared_memory_pool_len = framebuffer_size[0] * framebuffer_size[1] * @sizeOf(Pixel);

Now we can create and resize the file:

const shared_memory_pool_fd = try std.os.memfd_create("my-wayland-framebuffer", 0);

try std.os.ftruncate(shared_memory_pool_fd, shared_memory_pool_len);

Step 3: Creating the memory pool

Step 3 is much more complex. We are sending message to Wayland compositor (which is easy), but this time we must attach the shared memory pool file descriptor to a control message. So while the protocol definition looks simple:

wl_shm::create_pool(id: new_id<wl_shm_pool>, fd: fd, size: int)

It will require an entirely separate code path to send. I’m going to split it out into a separate function so we can clearly see what it requires:

/// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_shm:request:create_pool

const WL_SHM_REQUEST_CREATE_POOL = 0;

/// This request is more complicated that most other requests, because it has to send the file descriptor to the

/// compositor using a control message.

///

/// Returns the id of the newly create wl_shm_pool

pub fn writeWlShmRequestCreatePool(socket: std.net.Stream, wl_shm_id: u32, next_id: *u32, fd: std.os.fd_t, fd_len: i32) !u32 {

_ = socket;

_ = wl_shm_id;

_ = next_id;

_ = fd;

_ = fd_len;

return error.Unimplemented

}

First we’ll get the current value of next_id:

const wl_shm_pool_id = next_id.*;

But we’ll leave incrementing it until we know the message has been sent:

// Wait to increment until we know the message has been sent

next_id.* += 1;

return wl_shm_pool_id;

Next, we’ll create the body of the message:

const wl_shm_pool_id = next_id.*;

const message = [_]u32{

// id: new_id<wl_shm_pool>

wl_shm_pool_id,

// size: int

@intCast(fd_len),

};

If you’re paying close attention, you’ll notice that our message only has two parameters in it, despite the documentation calling for 3. This is because fd is sent in the control message, and so is not included in the regular message body.

Creating the message header is the same as in a regular request:

// Create the message header as usual

const message_bytes = std.mem.sliceAsBytes(&message);

const header = Header{

.object_id = wl_shm_id,

.opcode = WL_SHM_REQUEST_CREATE_POOL,

.size = @sizeOf(Header) + @as(u16, @intCast(message_bytes.len)),

};

const header_bytes = std.mem.asBytes(&header);

Instead of writing the bytes directly to the socket, we create a vectorized io array with both the header and the body:

// we'll be using `std.os.sendmsg` to send a control message, so we may as well use the vectorized

// IO to send the header and the message body while we're at it.

const msg_iov = [_]std.os.iovec_const{

.{

.iov_base = header_bytes.ptr,

.iov_len = header_bytes.len,

},

.{

.iov_base = message_bytes.ptr,

.iov_len = message_bytes.len,

},

};

Before we continue, we must make another detour to define the cmsg function. In C, CMSG is a set of macros for creating control messages. In zig, I have it generate an extern struct with the correct layout, and a default value for the length field.

fn cmsg(comptime T: type) type {

const padding_size = (@sizeOf(T) + @sizeOf(c_long) - 1) & ~(@as(usize, @sizeOf(c_long)) - 1);

return extern struct {

len: c_ulong = @sizeOf(@This()) - padding_size,

level: c_int,

type: c_int,

data: T,

_padding: [padding_size]u8 align(1) = [_]u8{0} ** padding_size,

};

}

With the cmsg function in hand, we can return to writing the writeWlShmRequestCreatePool function.

// Send the file descriptor through a control message

// This is the control message! It is not a fixed size struct. Instead it varies depending on the message you want to send.

// C uses macros to define it, here we make a comptime function instead.

const control_message = cmsg(std.os.fd_t){

.level = std.os.SOL.SOCKET,

.type = 0x01, // value of SCM_RIGHTS

.data = fd,

};

const control_message_bytes = std.mem.asBytes(&control_message);

SCM_RIGHTS is a unix domain socket control message that will duplicate an open file descriptor (or a list of file descriptors) over to the receiving process.

We now have all the pieces we need to assemble a std.os.msghdr_const struct:

const socket_message = std.os.msghdr_const{

.name = null,

.namelen = 0,

.iov = &msg_iov,

.iovlen = msg_iov.len,

.control = control_message_bytes.ptr,

// This is the size of the control message in bytes

.controllen = control_message_bytes.len,

.flags = 0,

};

Then we send the message and check that all of the bytes were sent:

const bytes_sent = try std.os.sendmsg(socket.handle, &socket_message, 0);

if (bytes_sent < header_bytes.len + message_bytes.len) {

return error.ConnectionClosed;

}

The full functions look like this:

/// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_shm:request:create_pool

const WL_SHM_REQUEST_CREATE_POOL = 0;

/// This request is more complicated that most other requests, because it has to send the file descriptor to the

/// compositor using a control message.

///

/// Returns the id of the newly create wl_shm_pool

pub fn writeWlShmRequestCreatePool(socket: std.net.Stream, wl_shm_id: u32, next_id: *u32, fd: std.os.fd_t, fd_len: i32) !u32 {

const wl_shm_pool_id = next_id.*;

const message = [_]u32{

// id: new_id<wl_shm_pool>

wl_shm_pool_id,

// size: int

@intCast(fd_len),

};

// If you're paying close attention, you'll notice that our message only has two parameters in it, despite the

// documentation calling for 3: wl_shm_pool_id, fd, and size. This is because `fd` is sent in the control message,

// and so not included in the regular message body.

// Create the message header as usual

const message_bytes = std.mem.sliceAsBytes(&message);

const header = Header{

.object_id = wl_shm_id,

.opcode = WL_SHM_REQUEST_CREATE_POOL,

.size = @sizeOf(Header) + @as(u16, @intCast(message_bytes.len)),

};

const header_bytes = std.mem.asBytes(&header);

// we'll be using `std.os.sendmsg` to send a control message, so we may as well use the vectorized

// IO to send the header and the message body while we're at it.

const msg_iov = [_]std.os.iovec_const{

.{

.iov_base = header_bytes.ptr,

.iov_len = header_bytes.len,

},

.{

.iov_base = message_bytes.ptr,

.iov_len = message_bytes.len,

},

};

// Send the file descriptor through a control message

// This is the control message! It is not a fixed size struct. Instead it varies depending on the message you want to send.

// C uses macros to define it, here we make a comptime function instead.

const control_message = cmsg(std.os.fd_t){

.level = std.os.SOL.SOCKET,

.type = 0x01, // value of SCM_RIGHTS

.data = fd,

};

const control_message_bytes = std.mem.asBytes(&control_message);

const socket_message = std.os.msghdr_const{

.name = null,

.namelen = 0,

.iov = &msg_iov,

.iovlen = msg_iov.len,

.control = control_message_bytes.ptr,

// This is the size of the control message in bytes

.controllen = control_message_bytes.len,

.flags = 0,

};

const bytes_sent = try std.os.sendmsg(socket.handle, &socket_message, 0);

if (bytes_sent < header_bytes.len + message_bytes.len) {

return error.ConnectionClosed;

}

// Wait to increment until we know the message has been sent

next_id.* += 1;

return wl_shm_pool_id;

}

fn cmsg(comptime T: type) type {

const padding_size = (@sizeOf(T) + @sizeOf(c_long) - 1) & ~(@as(usize, @sizeOf(c_long)) - 1);

return extern struct {

len: c_ulong = @sizeOf(@This()) - padding_size,

level: c_int,

type: c_int,

data: T,

_padding: [padding_size]u8 align(1) = [_]u8{0} ** padding_size,

};

}

Now we can return to the main function and create the memory pool:

// Create a wl_shm_pool (wayland shared memory pool). This will be used to create framebuffers,

// though in this article we only plan on creating one.

const wl_shm_pool_id = try writeWlShmRequestCreatePool(

socket,

shm_id,

&next_id,

shared_memory_pool_fd,

@intCast(shared_memory_pool_len),

);

Step 4: Allocating a framebuffer

Step 4 is much simpler. We need to send the wl_shm_pool::create_buffer request to specify the size and format of our framebuffer.

wl_shm_pool::create_buffer(

id: new_id<wl_buffer>,

offset: int,

width: int,

height: int,

stride: int,

format: uint<wl_shm.format>,

)

It has a lot of parameters, but they don’t require any funky control messages to send:

// Now we allocate a framebuffer from the shared memory pool

const wl_buffer_id = next_id;

next_id += 1;

// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_shm_pool:request:create_buffer

const WL_SHM_POOL_REQUEST_CREATE_BUFFER = 0;

// https://wayland.app/protocols/wayland#wl_shm:enum:format

const WL_SHM_POOL_ENUM_FORMAT_ARGB8888 = 0;

try writeRequest(socket, wl_shm_pool_id, WL_SHM_POOL_REQUEST_CREATE_BUFFER, &[_]u32{

// id: new_id<wl_buffer>,

wl_buffer_id,

// Byte offset of the framebuffer in the pool. In this case we allocate it at the very start of the file.

0,

// Width of the framebuffer.

framebuffer_size[0],

// Height of the framebuffer.

framebuffer_size[1],

// Stride of the framebuffer, or rather, how many bytes are in a single row of pixels.

framebuffer_size[0] * @sizeOf(Pixel),

// The format of the framebuffer. In this case we choose argb8888.

WL_SHM_POOL_ENUM_FORMAT_ARGB8888,

});

And now we have a wl_buffer that we can render into.

Rendering a Gradient

We’ve created a toplevel surface and a framebuffer, now we must combine the two to render something to the display.

This section is unfinished.

Links

- Wayland Explorer: An site that makes the Wayland protocols easy to browse

- zig-wayland-wire: The library I wrote while learning enough to write these articles.

- zig-wayland-wire/examples/00_client_connect: This is the code you should have be the end of this series

- How to Use Abstraction to Kill Your API - Jonathan Marler - Software You Can Love Vancouver 2023: A talk given by John Marler that covers a similar topic to this series, but for X11.